Patterns, from my Stranger Lives series, is now in the collection of the Columbus Museum of Art. Feeling grateful.

YALE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY ACQUISITION

I'm using paint and I'm psyched

A Nod is as Good as a Wink

A Nod is as Good as a Wink

Written by Lily Siegel

On the occasion of The Reality Principle

A two person exhibition with Karin Davie

at Pazo Fine Art in Washington, DC

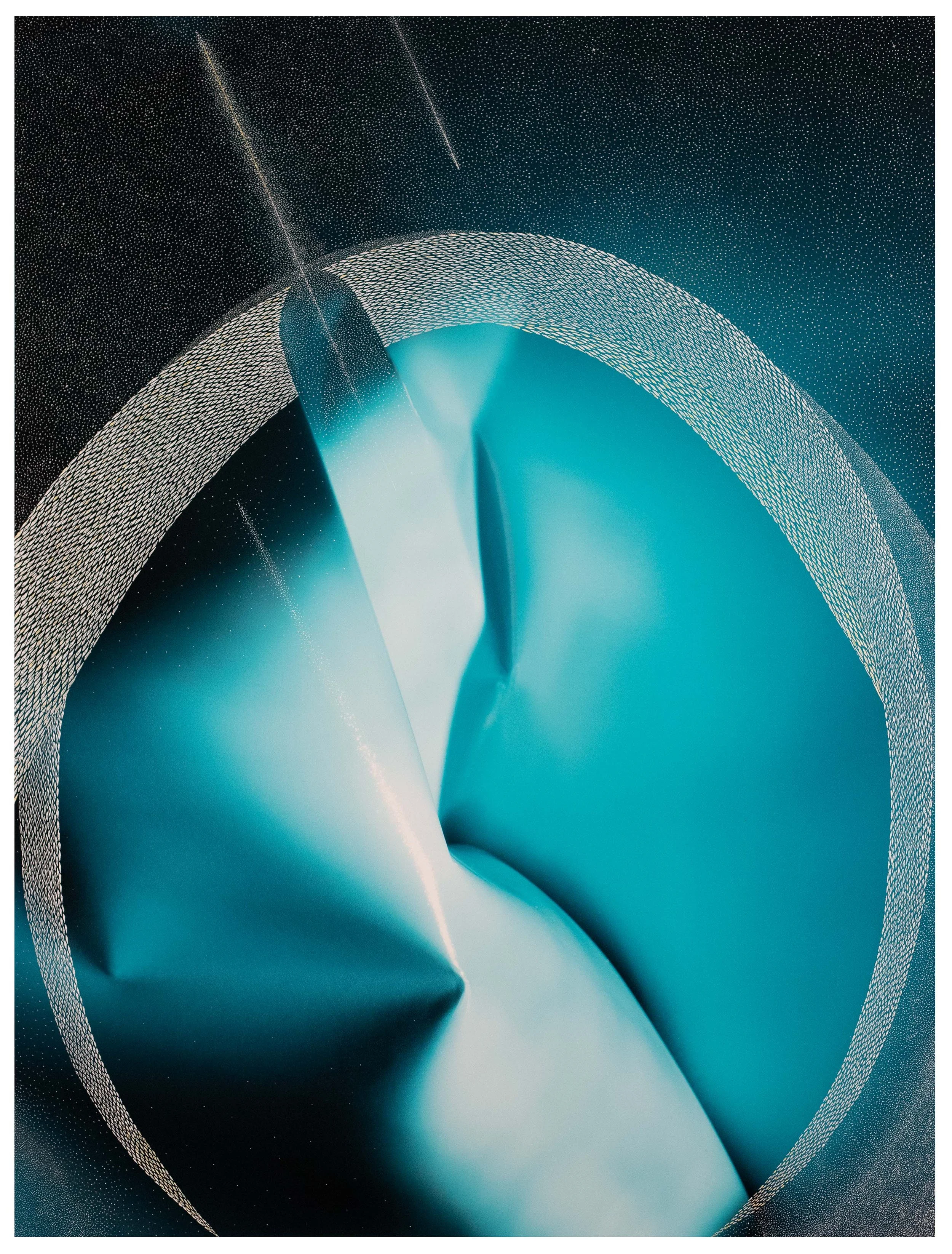

Caitlin Teal Price’s Dune (2023) might just be the perfect anchor for the two-person exhibition, with Karin Davie, The Reality Principle. If we assume that Price is referring to the landform, not the books/movies that are so present in the popular imagination now (again), we envision a massive mound made of the tiniest of sand particles. Millions, billions, of grains one atop the other form something grand. If Price, however, titled the work after the book/movie, well, that works too.

Karin Davie’s painting series Beam Me Up (2019–2022), of which two works are included in the exhibition, are titled in direct reference to Star Trek. The works were first shown in an exhibition-in-two-parts titled To Boldly Go Where No Man’s Gone Before.

Science fiction could be a useful genre through which to consider these works. Like the genre, Price’s and Davie’s works are based in factual reality, but use speculation to arrive at a more human truth. Both artists’ work is firmly grounded in the physical: in an artist’s own body and an object’s own solidness. Though both artists work in formal abstraction, it is an abstraction inherited from artists, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Eva Hesse, Richard Tuttle, and Bruce Nauman, whose abstraction has discrete corporeal references. While Davie must steady her full body to achieve the desired repeating wavelike stroke over and over to produce one painting, Price focuses her control on thousands of small incisions on a single surface.

There is an often-repeated quote of O’Keeffe stating, “Nothing is less real than realism. Details are confusing. It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis that we get to the real meaning of things.”[1] Both Price and Davie worked for many years with more direct representations of the human figure. Their bodies were also always present in the work, as the artist lugging around the camera and accompanying equipment, in Price’s case, and through the length and tenor of the brushstrokes in Davie’s, the use of her own body in performance and multimedia works. As the obvious figure was eliminated as the subject of their works, the emphasis became the person in front of the picture—the artist, or even the viewer. That labor is in the image. The results are art works that depict something at once heavy and light.

As smaller cameras, digital printing, and life circumstances made the physicality of taking photographs less integral, Price found herself looking for ways to employ her body more fully in the making. She started taking long walks to gather objects, which led to mapping, which led to drawing. Effort is important. As the artist makes her mark on the paper, dust accumulates on the floor as she removes her material to reveal an image, which is often borrowed from historical photographs or quotidian household objects. The process, though, is not important except as the expression of the work to make the work.

Same for Davie. Two paintings in the show are titled In the Metabolic No. 5 and In the Metabolic No. 8. The process of metabolizing is a conversion to energy. This series of works is on linen over shaped stretchers that accommodate a cutout that originated as a disruption caused by the artists own impeding body. Because of this elimination, the painter must interrupt her fluid stroke with athletic precision to maintain the coherence of the picture she is painting. Breaks and impediments are important for Davie. The other works in the show are diptychs. The canvases so perfectly fit together that the zips down the middle almost seem negligible. However, just like the notches cut into the edges of other paintings, the break in the diptychs cause a disruption that forces one to do a double take. What looked like a mirrored image is not exact. It becomes uncanny, a bit like seeing oneself with your camera non-mirrored in a video conference. Gestures become heightened. They are perhaps the most important detail, the “real meaning of things.”

Back to the beam. Davie talks of her fascination with Nauman and his use of his body in the work he’s been making since the 1960s, especially those made with neon light and tubing. Nauman’s use of light was based in its material properties as delimiting physical space. His work The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign) (1967), a spiral of blue and red neon stating the title, is pointed and funny. Light, especially when present in artworks, is thought to represent the mystical. His bright window or wall sign advertising the service of the true artist is blatantly not revealing any mystic truths.

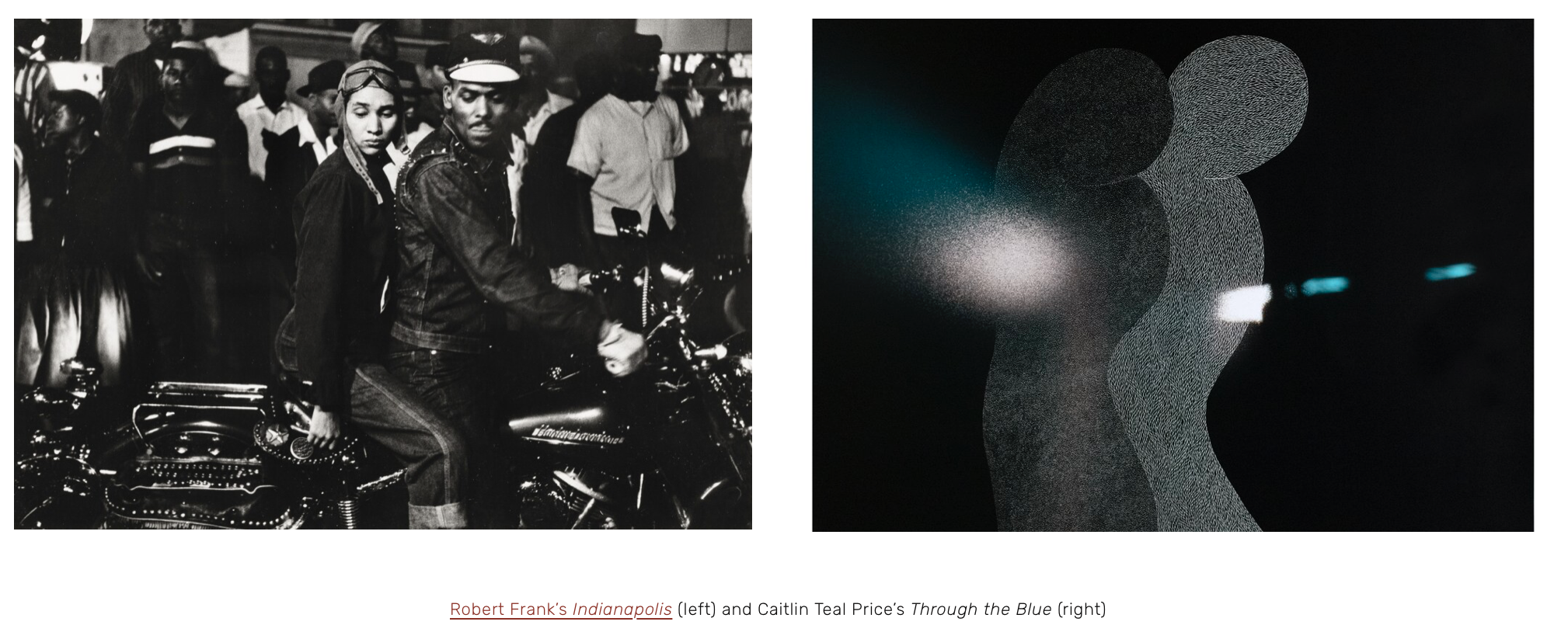

For Price and Davie, light is also used as a form that takes up space. It is something to move around. A photograph is a drawing with light; it is the act of capturing something that is seemingly ephemeral and turning it solid. Price comes from photography and draws atop photographic prints on Hahnemühle Rag paper. Davie’s use of light is more like Nauman’s use of neon—it becomes solid, a subject, an object, something to make room for. However, light is never the subject. It is a small part of the bigger point, an obstacle that one must get past or around to return to groundedness.

[1] “I Can’t Sing, So I Paint! Says Ultra Realistic Artist; Art is Not Photography—It Is Expression of Inner Life!: Miss O’Keeffe Explains Subjective Aspect of Her Work,” New York Sun, December 5, 1922, quoted in Jonathan Stuhlman, Georgia O’Keeffe: Circling Around Abstraction (Manchester, VT: Hudson Hills Press, 2007), p. 22.

Dune, 2023

X-acto blade etching and colored pencil on hahnemuhle rag paper

42x52 inches

The Reality Principle @ PFA

THE REALITY PRINCIPLE

Karin Davie & Caitlin Teal Price

PFA–Washington, D.C

April 6 - May 25, 2024

Opening reception: Saturday, April 6th, 6 - 8 PM

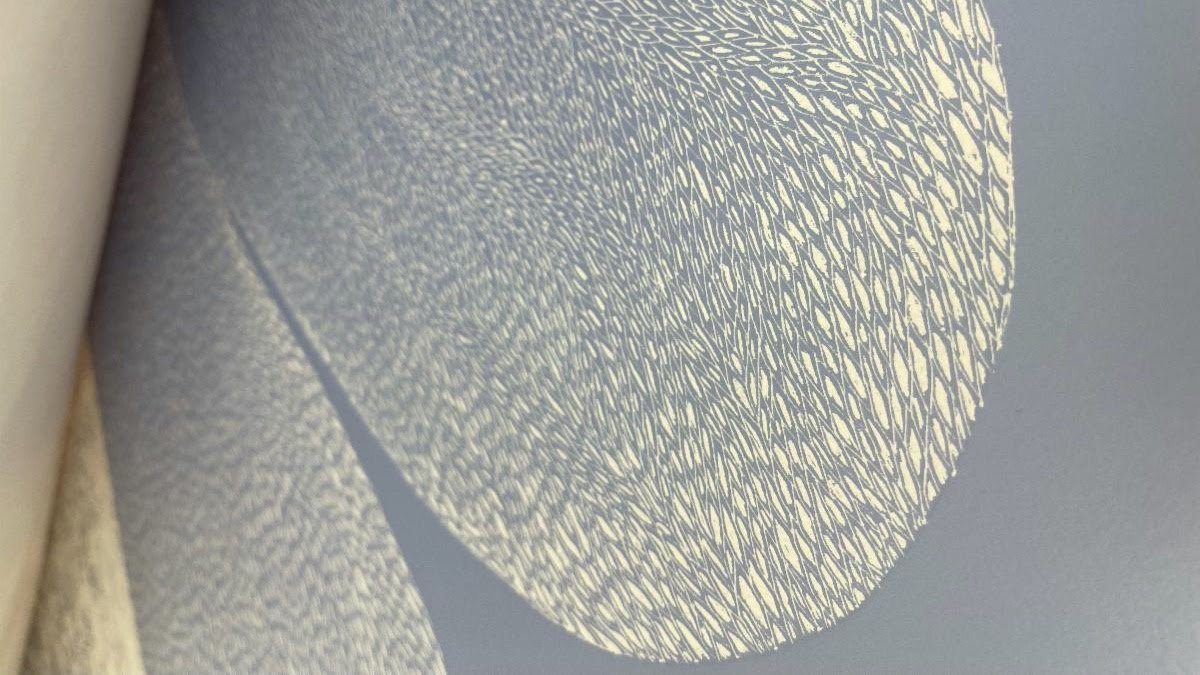

Caitlin Teal Price, Bue, 2022, x-acto blade etching and colored pencil on hahnemuhle rag paper, 30x40

PRESS RELEASE:

Davie and Price are driven by a shared commitment to form and the importance of process. The works featured in this exhibition present viewers with immersive, psychedelic, abstract terrains that embody the interplay between the micro and the macro, the material and the ephemeral. The careful manipulation of light, color and form could give the viewer the sense that they are looking through a microscope at cellular matter, or through a powerful telescope at intergalactic nebulae. There is a compelling optical contrast between the sense of infinite, deep space evoked by their works, and the tangible physicality of the surfaces they create.

Davie’s seven works featured in the show foreground her mastery of the repeated undulating wave form and gesture. In the larger works, this rhythmic motion skillfully accommodates the borders of her humorously shaped canvases, while in smaller works, it is explored through diptych formats. Price’s nine drawings demonstrate, across a range of sizes, her prowess in intricate, meticulous mark making interwoven with a distinctive use of the play of light. Each artist, grounded in their bodies, undertakes the task of creating with the heightened awareness and hyperfocus similarly required of an athlete. Davie must produce a brush stroke in one steady movement without any room for error lest she must return her surface to the base primer and begin again. Through the mediated layering of gestures, she arranges a series of syncopated waves around a central opening which, when paired with a skillful gradation of color, appears to emanate a shivering light. Price draws in an equally unforgiving procedure that involves incising millimeter-length lines and gouges into a photograph. Her works explore a temporal tension between the capture of a fleeting, almost mischievous instant of natural light and the intensive, tactile labor of etching. Combining these aspects of her process “takes something fluttering and hard to nail down, and puts the concreteness of the physical body back into it.” Stepping back from the intimate, bodily surfaces fashioned by the artists’ concentrated physical mark making, the cosmic scenes remind the viewer of bodies, space, architecture, interiors and exteriors. The key to understanding each artist’s work is physical, substantial, presence.

The Reality Principle refers to the classical psychoanalytic theory of ego regulation; the ability to delay gratification through impulse control and rational thought (a maturing of “The Pleasure Principle,” which compels us to act in pursuit of immediate gratification.) Through controlled, disciplined and choreographed gestures rooted entirely in the concrete and the physical, Davie and Price’s works can make us feel transported to an intangible, metaphysical elsewhere.

An essay by art historian and curator Lily Siegel will accompany this exhibition.

Karin Davie, Traveling solo No. 2 (diptych) 2023, oil in linen, 54x30in.

into the day, through the night @ Sarasota Art Museum

This work is part of a larger group exhibition tilted The World is Smarter Than You Are, honoring the late and great Richard Benson. Curated by Peter Barberie, Brodsky Curator of Photographs, Alfred Stieglitz Center, Philadelphia Museum. The exhibition also includes artists: Dawoud Bey, Lois Conner, Jen Davis, An-My Lê, John Lehr, Andrea Modica, Arthur Ou, John Pilson and Sarah Stolfa.

A large, three panel commission in Houston, TX

For the first six month of 2022 I was working on a large scale commission for the lobby of Two Allen Center in Houston, TX. I worked closely with Kimberly Landa and Kinzelman Art consultants to make it happen. below is an interview I did with them about the project.

KAC ARTIST Q&A

Over the course of the past year, Kinzelman Art Consulting has partnered with Brookfield Properties to select an artist to commission a custom work for their newly renovated lobby in Two Allen Center located in Downtown, Houston.

"The lobby of Two Allen Center is a central location for Allen Center, making this an important moment to engage campus employees and visitors. Working with Kinzelman Art Consulting made for a smooth process from art direction to development and final installation. We are pleased to feature this original piece as a new focal point in the lobby, and thank KAC for helping to bring this vision to life. Caitlin Teal perfectly captured the essence of the space."

-Tyler Merritt, Vice President, Asset Management

The artist, Caitlin Teal Price from Washington DC, was selected to fulfill the commission of a large work to be placed in the reception area of the Two Allen Center building. Caitlin traveled to Houston this month to meet the KAC team and install her site-specific work. We sat down with Caitlin to ask about her working process and experience with the commission.

Artist Caitlin Teal Price at Two Allen Center

[KL]: How did you arrive to your unique working process?

[CTP]: I believe it was in 2017 when I started working out the scratch drawings. Previously, I made most of my work away from home and out in the world. But by 2017 I was in the middle of a life transition, and more confined to my studio. I tried a number of ways to satisfy a new studio workflow, but it wasn’t until I started using an X-ACTO blade to etch into my photographic prints that I found my flow. The marks were very crude at first and I was unsure that it would work. But it turns out that I really enjoy the process, so I kept at it. The work has evolved and continues to evolve over time and with each piece. Now I use photographs with strong compositions as the jumping off point for the etched abstractions that I work into the print. I also now use different X-ACTO blades with varying degrees of dullness to get the variation in the marks that I make. From conception to completion each work takes over a month to create.

The Artist's studio in Washington DC

[KL]: Your process is so labor intensive and must require a lot of patience. Would you say it’s meditative? Stressful? Give us some insight into the mental/emotional aspect of your practice.

[CTP]: I would say that it is both meditative and stressful and sometimes confusing and often fun and satisfying. The work takes so long to make that I have a range of emotions when I’m in the middle of it. Before I start the piece, I figure out a general plan. I make a smaller study of the work and use it as a kind of map that I can reference as I make the full-size work. I expect the work to evolve and change from the original plan, so I leave myself open to that. As I work on the final piece, I need to be aware of what marks I am making, and I need to be able to anticipate what’s next. This technique of scratching into the print is unforgiving. I cannot undo the marks, so I need to be careful and deliberate when I make them. I find that its trouble when I get too lost in thought so most of the time, I am pretty focused. Because each piece requires such long periods of sitting or standing with the work, I listen to podcasts and music to keep me company.

TYart installing Caitlin's work in the Two Allen Center lobby.

[KL]: What made you decide on this particular composition and coloration for this project?

[CTP]: When figuring out the composition for this piece, I was thinking about the space it was going to hang and who was going to occupy that space. The placement of the tryptic is above the reception desk at Two Allen Center in a large, sunny, open, beautiful room connecting the three Allen Center buildings. It is a space where people pass though busily from one meeting to the next but also pause to recharge. It is a space of energy and of rest. I wanted the piece to reflect that by suggesting movement and ambition as the shapes rise and reach out of a place of rest. The blue works are a mirror of one another suggesting community and cooperation. The orange piece bridges and connects the left and right and reads as has both weighted and light at the same I chose the colors blue and orange because when combined they are energetic and surprising while at the same time familiar and comforting.

Caitlin Teal Price's site specific commission, "Untitled (reach to rest)" in Two Allen Center.

[KL]: What was your experience like collaborating with KAC?

[CTP]: It was amazing to have the opportunity to collaborate with KAC! When working on a commission, especially of this scale, it is so important that the vision of the artist is supported and trusted, and I love that Kimberly and Julie put that trust in me.

They supported me through the entire process and gave me the freedom to make the work that I envisioned, and I cannot thank them enough for that!

Object Lesson - On the influence of Richard Benson

I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from the late and great Richard Benson and honored to be a part of his legacy through this beautiful book published by Aperture. For the book, we were asked to write a bit about what we learned from Richard…

p. 142-143

I remember the time Richard invited me and our entire MFA class to his house. He showed us his garden, his book collection, his studio where he made both photographs and clocks. I wasn’t aware of Richard’s interest in clocks until that day. It took me by surprise because I only knew him as Richard Benson, Mater Printer and Photographer. As the ten of us stood in his studio facing a wall of clocks, surrounded by metal parts and plans drawn on scraps of paper, he said that clocks were the most complicated thing to build.

Richard was never intimidated by a challenge, and he followed his passion wherever it went. He had the ability to effortlessly flow from solving complex technical and artistic problems to the routine of his daily life – all while maintaining a contagious enthusiasm. As we sat down to lunch that day at his long kitchen table, Richard talked freely about his family, his children, and the adventures he had while traveling the country in his RV named Giraffe. Richard was authentically himself no matter what he did, and he made you love him for that.

As a student of Richard’s, I internalized his generosity, his energy, his discipline, his character. He taught me to think about art in the context of life; and that no matter how particular and exacting your work is, the most important thing is to be authentically yourself, in every aspect of your art, your life and especially when confronted with challenge.

In recent years, I have drawn upon the lessons absorbed during my time with Richard as I have needed to face and accept the uncomfortable and challenging shift in my identity from artist to artist – mother. I no longer have the same time and freedom to search for photographs as I had as a young artist and have needed to figure out a way to make important work while confined to the responsibilities of home. I often think about Richard and the fact that he never resisted challenge; how he could effortlessly weave the complexity of life into art. Rather than resisting the challenge of my situation, I am weaving the complexity of life into art by using photography and drawing – a new practice for me – to incorporate the constraints of the quotidian in an investigation of domesticity, routine, ritual, and play. In this work, Scratch Drawings, I photograph sunlight coming through the windows of my home as it shines onto colored paper. The overlaid shapes, created by etching into the photograph with thousands of minute x-acto blade marks, are abstractions of photographs found, seen, and created in the everyday. Just as Richard would have expected of me, I’ve embraced the challenges I face to make work that is uniquely, authentically, and painstakingly my own.

Philadelphia Museum of Art Acquisition

I feel very honored to have this piece acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and super grateful for their support of my work!

Untitled (waiting for), 2021, 30x40 inches, x-acto blade etching on photographic print.

Detail of Untitled (waiting for), 2021, 30x40 inches, x-acto blade etching on photographic print.

PROCESS SPOTLIGHT

Written by Whitney Cole // Candela Gallery

Washington DC-based artist, Caitlin Teal Price has not always been so experimental with the photograph as an object; the artist returned to the tactile process after the birth of her second child led her to seek out a more “WFH”-friendly photographic workflow. In fact, Scratch Drawings is quite a step away from the glistening, tanned beach bodies of Stranger Lives or the cinematic women of Annabelle, Annabelle.

Visually, these career phases can be bridged with a clear passion for photographic structure: light, texture, and color. However, in conversations about the newer work, Price expressed a fatigue with the digital process; there’s significantly less magic with the push of a button than the materialization of the latent image in a dark room bath, or the excitement of having really created a unique object. She wanted to return to a more manual, individualistic process with her works.

After a serendipitous divergence into mark-making, Price began combining her love for light and the intimacy of the mark into the foundation of her work today.

Price’s process begins by combing through seminal photo history books, making gestural tracings of familiar forms that draw her eye. Parallel to this process, Price captures imagery of falling light coming through the old windows of her home on colored papers, creating small backdrops for the fleeting shapes. Next, she returns to the sketches and begins to pair the drawn forms and the captured images. Finally, she makes several studies of these pairings on 11x14 paper, using x-acto blades of varying sharpness to carve into the surface of photographic prints made from the colored light. Eventually, the perfect match is found, and she uses the chosen study as a reference for the larger, unique piece. Each final piece can take up to two months of meditative mark-making with an x-acto.

Over time, the work has evolved from Lego shapes from her sons’ toys to the more abstracted forms we see today. Price has introduced pencil as a way to add more dimensionality to the white of the re-exposed paper, and has begun making an even more conscious effort to allow the markings and the light to weave together and support one another.

Though Scratch Drawings initially feels like a stark departure from the photographic process, it serves more like a deconstructed ode. Each color chosen is a nod to the RGB/CMYK color scale; the scratched textures themselves are pulled from photography’s past; light, the queen of photography, is glorified with a straight portrait.

Written by Whitney Cole // Candela

Scratch Drawings, the Catalogue

2021 Limited Edition SIGNED Catalog

Scratch Drawings by Caitlin Teal Price

Edition of 100, individually numbered

Published by Candela Books

$35

SCRATCH DRAWINGS @ CANDELA GALLERY / RICHMOND , VA

Candela Gallery is excited to mount its first solo show by Washington, DC-based artist, Caitlin Teal Price. Through photography and deliberate, delicate mark-making, Price carves gestural patterns and shapes into the surface of her prints. Built on photographs of sunlight, seeping through the windows of her home, these Scratch Drawings are an exploration of the ritual and routine found in the undercurrents of Price's daily life.

The thousands of marks found on Price's light reflections reference photographs of the everyday taken by Price herself as well others, including Lee Friedlander and Robert Frank. After several months of laborious mark-making with an x-acto blade, Price's large-scale works transcend to abstract scenes of playful figures and gestural landscapes, manifesting and exploring themes of motherhood and the quotidian. Scratch Drawings will open Friday, November 5th, from 5-8 pm. The exhibition will be on view through December 21st, 2021. Featured works will also be included in a printed catalog published by Candela Books.

CTP on the beach photographing for Stranger Lives, 2013

photograph by Chloe Apple Seldman

Kaitlin Booher and I talk about Stranger Lives!

Kaitlin Booher : Hello Caitlin! Let’s start at the beginning, what is Stranger Lives?

Caitlin Teal Price : Stranger Lives is a series I worked on for two weeks every August between 2008 and 2015. I would walk the beaches at Coney Island and Brighton Beach from noon until 2 pm when the sun was hot and high, so I could get glistening bodies and sharp focus. I wanted to capture every little detail that I could. The work itself is about the lives of these strangers—what you can discern about a person from the markings on their bodies, their scars, wrinkles, and the objects they surround themselves with—that is what drew me to making this work, and it was those details that motivated me to approach so many people over such a long period of time.

KB: You’ve spoken elsewhere about how you would wear a red dress and try to make yourself visible but disarming when asking people’s permission to photograph them. But you were photographing with a bulky, professional-looking camera. Do you think your camera played a role in your interaction with strangers?

CTP: I would notice other photographers; they were mostly men with telephoto lenses strapped around their neck walking along the shore taking pictures of people splashing in the waves or something. So, I think in general, I didn’t blend in with typical beach photographer. I used a Mamiya RZ-67 medium-format camera which is quite large and does present as official. It is unusual to see a woman carrying one on her hip through crowds of sunbathers. I think my camera helped me stand out, which was part of my strategy with the red dress, too. I wasn’t a creepy photographer but a recognizable regular on the beach, which in my mind made me less threatening, which in turn made me feel more comfortable approaching strangers. I think that confidence helped put people at ease.

One thing I love about this series is the uniformity of the composition of your photos, because it makes the diversity of bodies, adornments, and clothing stand out. How soon did you figure out the scope of this series? Was there one photo that set the format for the rest?It took me a few weeks to figure it out. At first, I was really interested in couples whose bodies were intertwined with one another and showing affection in public, each image was different. But I quickly realized that strangers on their own were endlessly interesting and that I didn’t need to introduce the relationship aspect. I have always been attracted to typologies, so I zeroed in on the format quickly after that.

It's striking how everyone’s eyes are closed. How much would you need to direct people? Would people ever want to smile or pose?

I only approached people who were already lying on their backs. So, they were naturally posed for the photograph before I spoke to them. I would never ask them to move. And I never moved anything around them. Once they agreed to be photographed—and about 50% of the people I approached did —all I asked them to do was close their eyes and ignore me. Sometimes people wanted to pose, or they instinctually would, but I would encourage them to relax. I think this series would be completely different if the strangers’ eyes were open. A different relationship occurs when there is eye contact.

The guy in the white speedo breaks the mold.

Yeah, he does, and there are a few that do. It bothered me for a while that he struck a pose, but the picture still works and in the end that’s what matters.

What is particular or special about the people at Coney Island and Brighton Beach? Did you photograph sunbathers in other places?

I went to Miami and to a few beaches in California, but they were never as fruitful. For a few reasons, I think. One, those beaches were simply not as packed. In New York you have this the density of people who just flow off the Subway and onto the beach. There is also a rawness in New York that I didn’t find in other places. People in New York are used to being in their own worlds, not caring what people around them think. They are ok with who they are, with presenting themselves in public without too much thought sometimes. And in New York especially, the beach is a place where you can let it all hang out. The other thing about New York is that it’s such a melting pot. There are SO MANY different types of people and I was looking for all types of people.

And for New York City dwellers living in tiny apartments, public space is ironically an important private space. Combine this with the universal strangeness of the beach as public space.

Going out and getting space in New York is a really big thing. Of course, the beach is unlike any other public space because you take off your clothes and sleep. It is weird to photograph someone with clothes on at the beach. I've got [images of] a couple people who are fully clothed and they look totally out of place.

Would people be confused when you approached them?

Some were confused, some were just blissed out. I never knew what I was going to get. I would walk over to someone and just be as nice as possible. I smiled a lot. I would crouch down, and say: “excuse me, I’m a photographer photographing people laying on the beach and you look perfect. Do you mind If I take your picture? You can close your eyes and totally ignore me. I’ll be gone in a second.” Sometimes they would sit up and talk to me, sometimes they would just say yes and close their eyes and ignore me, and sometimes they would tell me to scram! After I made the picture, some would ask to see it, because they assumed it was digital, but it was film, so no one ever saw the image. And I never followed up because I wanted to keep everyone as strangers. That was part of it for me. I wanted to learn about these people through the image.

Of course, for artistic purposes such as yours, you did not need a model release.

I thought about this a lot. But in the end I figured, they are in public, I asked permission, Philip- Lorca diCorcia went through that lawsuit and won.. At the time, I thought that asking for a release would have been even more intrusive. It would have raised more eyebrows and would have elicited more questions. I wasn’t trying to be sneaky. It just would have been too much. I really didn’t want to disturb these people more.

There’s an ethics to that. Plenty of street photographers working in a similar location--I’m thinking of Lisette Model in the 1940s--would just go ahead and photograph people who were asleep and unaware.

I couldn’t have done this without asking. My camera had to be focused, and I would stand so close to the subjects, so it’s already so intrusive. The dudes walking the beach with long lenses were different.

Has anyone ever recognized themselves or friends and gotten in touch with you?

No one has ever recognized themselves or got in touch.

I feel like they will eventually! In the last decade or so, women in Robert Frank or Garry Winogrand’s photographs have recognized themselves.

Let’s talk about the title Stranger Lives. Did it come to you immediately?

I was calling it “Washed Up” for a long time, because in addition to strangers I was interested in the intersection between life and death and the subtext in my mind as I was talking along the beach was that these bodies were washed up on the sand. These people were in their casket, and this is how I can tell who they are. But those ideas were a bit too dark and I eventually started seeing them as alive and well strangers! For the record, I did adopt this title before the show Stranger Things came out!

Were you ever tempted to zoom out and depict more of the beach, or some of the iconic amusement park?

I took a couple of pictures with Coney in the background, but for the series I didn’t want to give the images a place. I wanted to keep the images about the specific person and not the whole environmental context.

The small details are what amaze me about these images, and they continue to reveal themselves the longer you look at them. Even after looking at them hundreds of times, it was only when I was printing them that I noticed certain things. There are layers of reveal, which I think is pretty cool.

I thought there was a bigger pool of images, given the duration of this series!

Yeah, some days I would only ask 5 or 6 people for a photograph and only 2 of them would say yes. It was not easy to get the images and I was very selective with who I decided to approach. It was like casting for me. And I really only asked people who I was interested in. Over the course of the summer I could get anywhere from 10-15 new pictures and now there are about 75 in the series.

Did you ever photograph the same person twice?

Yes! A few times. Twice was on purpose. I had seen them in previous years, they were nice and the pictures I got of them weren’t great, so I asked again. They both said yes a second time! That was nice. Another time was not on purpose. I approached this girl with the most amazing nails and she said, “you photographed me yesterday!” That was embarrassing. I saw so many people it was hard to keep track sometimes. I was always scared I would ask someone who had already said no.

What about the images of two or more people? I’m looking at this photo of two girls in the pink bikinis who are almost twins and wearing lots of makeup.

Interactions between two people was re-introduced probably in the last year or two that I was making these pictures. I started re-thinking about pairs of people, and how a significant other or a friend can become a kind of prop in your life. The pairs of people usually focus on one of the two people in the frame.

The people we surround ourselves with play a big role in defining our lives and roles, in the same way that we fashion and define ourselves through clothes and belongings. It’s all a way of communicating who you are to the world.

I totally agree. I explored that theme in my series Annabelle, Annabelle too, which actually arose out of the Stranger Lives pictures. In Annabelle, Annabelle the images of woman are staged and every one of them has a prop, something I planted, that communicated a hint of who these characters were.

Interesting! And I think you can draw a line from Stranger Lives to the abstractions you’re currently making, in terms of light and color and form.

You totally can, there’s a progression and it makes sense. Unless you’re versed in art it’s hard because they look so different. With all my series, it’s particular to a certain time in my life and what’s going on, but they’re exploring the same themes in different visual ways. And now I’m making abstract pictures based on photographs, making abstract shapes from daily life, which comes back into themes about the spirit, light, form.

And the strangers depicted are, on some level, abstractions of real people.

Absolutely, we see one little moment in a complicated life. Its totally abstracted from reality. In a visual way, if you block out details, you get shapes that move towards abstraction, which is something I was thinking about as I was laying out my book. It’s also something I am thinking a lot about with my work today. Its a thing in and of itself.

The subject’s positioning in space can seem disorienting.

I can see why you say that. Some people want to see them vertically and I think it’s because we are used to seeing people standing upright. But, for me when you look at them vertically, they are even more disorienting.

Stranger Lives will be a particular marker of a specific time, like photographs made at Coney Island in the 1940s. I’m thinking of Weegee’s image of the crowds there during a heatwave or photographs that Lisette Model or Sid Grossman took of people swimming and hanging out on the beach.

I think so, the way people dress and sunbathe is already changing and the work is already aging – for instance, there are plastic bags everywhere and there aren’t a lot of phones. Honestly, I don’t know if people would let me photograph them like this today. Social media has really changed things. When I began the series in 2008, I didn’t have a smart phone and I certainly wasn’t on Instagram. I wonder if people would say yes today, or if I would have the same amount of luck as when I was making the work originally.

You worked on this project for a long time, 2008 to 15, how did you know when it was complete?

When I made the book [published by Capricious] in 2016, I felt like it was a good time to end. I had made 90+ pictures, I had two kids, it was harder to do it the project. I had to say “OK, this is it.” I could have kept going, but I like it as a time capsule now.

After a year of social distancing, how does it feel to revisit this series?

The exhibition So Hot You Could Fry an Egg is about the summer and heat. After having such an intense year, having a show that’s the opposite is fun. I think about this work and how it aged, I've always thought about how it will look in 10 years, now it is starting to seem like a marker of a specific, pre-Instagram time.

It is also nice to see these prints installed in a gallery, in person. The prints themselves are life-size, so it can feel sort of voyeuristic. Something uncomfortable can happen for the viewer, it’s like you can’t look and you can’t look away, and I think this is an effect of them being so large.

Kaitlin Booher is an independent curator and Ph.D. candidate in art history at Rutgers University. She is currently the Jane and Morgan Whitney Fellow in the Department of Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

New DC Art Studio Will Help Artists Connect

NBC Washington Channel 4

The new STABLE Arts studio in D.C. will help artists connect and make friends. Aimee Cho reports.

(Published Thursday, Oct 10, 2019 | Credit: Aimee Cho)

A warehouse of their own: D.C. artists launch a co-working and exhibition space

The Washington Post

By Tara Bahrampour Oct. 11, 2019 at 5:18 p.m. EDT

For the past four years, as Melvin Nesbitt Jr. was coming up as a professional artist, he managed to find space in which to work. But he had a harder time finding a supportive network of fellow artists to help connect him to the larger professional scene.

A collage artist who lives in Shaw, Nesbitt, 46, applied for a spot at STABLE, a studio complex and exhibition space in Eckington that opened its doors this summer to 32 artists from around the Washington metro area.

Since then, “I’ve been offered to teach a couple of workshops and got a solo show through my association with STABLE,” Nesbitt said. “I knew this was going to be a community, and the other artists were very interested in being part of a community and interacting with each other, and that’s something I felt was missing in my life as an artist before.”

Creating a hub for artists in a city not generally associated with the concept was the primary goal of the nonprofit organization, founded by three artists — Tim Doud, Linn Meyers, and Caitlin Teal Price — who moved to the District after achieving success in other cities. Determined to counter the common wisdom that Washington was no town for artists, they set out to create a meeting ground similar to those that had helped them flourish in New York City and elsewhere.

The 10,000-square-foot space, housed in a sprawling brick building that was once a stable for a Nabisco factory, includes 21 studios for 24 artists, a shared workspace for eight more, a lounge and a 1,100-square-foot gallery space.

The artists, selected from among 150 applicants by a panel of arts professionals, range in age from their 20s to their 60s. Some have decades of experience; others are relative newcomers.

The space officially opens next week with an inaugural exhibition showcasing the work of its artists and a fundraising dance party. Some of the pieces on display refer to the District — either directly, such as the wall of giant letters reading “GO-GO BELONGS HERE,” by Nekisha Durrett, or more obliquely, such as “The Tran-harmonium, A Listening Station,” by Emily Francisco, in which 88 keys of a piano are hooked up to 43 radios tuned to different stations. In St. Louis, where Francisco used to live, that meant a lot of country music; in Washington the device captures more news.

Francisco’s studio is 163 square feet, but she built sturdy shelves into the top half to accommodate materials such as piano innards and old televisions.

Other spaces are larger, and some are shared. In a spacious loft, Andy Yoder, 61, worked on a giant fence rail plastered with real tobacco leaves and wrapped in plaid flannel, with roots at the bottom of the posts.

Yoder lives in Falls Church, Va., but the piece also reflects his childhood in Ohio horse country, “looking in from the outside at that equestrian, horsy, kind of preppy culture.” Pointing at the roots on the bottom, he said, “As fence rails sometimes do, they’ll kind of sprout new sprouts.”

When Yoder moved to the Washington area five years ago, he had trouble connecting with other artists.

“I lived in New York City for about five years, and I just had not found my tribe in this area,” he said. “In New York you’re always in conversation with other artists by putting your work out there. . . . Artists are like orchids — they need a little terrarium to thrive. There’s nothing like having other artists around you.”

For Yoder, that need has been met by sharing a studio space with Nesbitt. “I make suggestions and he gives me feedback,” Yoder said. “It’s just helpful having another set of eyes.”

Nesbitt, who is originally from Spartanburg, S.C., moved to the District 16 years ago to be with his partner. His collage-on-cardboard work features landscapes and portraits based on the housing project where he lived in elementary school. One 5-by-4-foot piece depicts two young African American boys sitting on a couch beside a man holding food stamps whose head has been replaced by the head of Uncle Sam.

The picture is based on Nesbitt’s own childhood and how it was affected by government policy.

“If there was an able-bodied adult man in the house, benefits would be cut off,” he said. Even after that rule ended, he said, “many jurisdictions down South would use it to intimidate people, and for years people believed that it was an enforceable law.”

“I once heard someone refer to the welfare system as ‘White Daddy,’ ” Nesbitt said, adding that when he was a child his father did not live with him in part because of fear that benefits would be cut off. The painting was an attempt “to acknowledge that this dad, our dad, was replaced by a welfare check.”

Not all the STABLE artists have physical studios. Eight were selected to be part of “Post Studio,” a co-working space similar to WeWork, for artists who either already have studios but want to be part of the STABLE community or who don’t need traditional studios. This group comprises visual artists and writers, including a sculptor, Mary Hill, who is currently in law school and whose piece on display, “Ethical Problems,” is a law book cast from brightly colored silicone.

One of Post Studio group’s artists, Aziza Gibson-Hunter, 65, has worked as an artist since coming to Washington 30 years ago to study printmaking at Howard University. She said she appreciates the connections she makes with younger artists at STABLE.

“I learn from their ideas,” she said. “And as a person of color I can bring my cultural experience to this, which I think is important because the artists’ organizations can get very insular.”

Most artists will have the opportunity to renew their one-year leases, for which they pay based on the number of square feet. But the facility also has spaces for visiting artists who may come for shorter periods. The founders hope to bring them in in collaboration with Washington’s embassies, many of which are interested in spreading culture across international borders.

STABLE has also had representatives from museums and galleries around the country come to visit, such as the one who will be installing Nesbitt’s solo show this December at Sense Gallery on Georgia Avenue NW.

“I think I’ve had more people coming through here than I did in five years of home visits,” said Molly Springfield, 42, an artist who lives in Adams Morgan.

That is a perk that wasn’t necessarily planned, Meyers said. “Originally we were really focused on the artists’ needs for space to work but as the project evolved we came to understand that there were collectors and curators and others who really longed for access to the studios of the art-making community.”

Standing in the cavernous space behind the studios where they were preparing for the dance party, Price had a huge smile. “Some days I’m blown away that we actually did it,” she said.

STABLE OPENS ITS DOORS IN ECKINGTON

Brightest Young Things

By KAYLEE DUGAN AND CLARISSA VILLONDO OCTOBER 15, 2019

Last January I spent an hour sitting on the floor of 336 Randolph Place NE, pouring over maps, talking about Kickstarter fundraising and spending an hour or two living in Tim Doud, Caitlin Teal Price and Linn Meyers vision. As they led me down corridors that didn’t have electricity and showed me empty, concrete rooms that were full of light, I could start to see the outline of their dream. A little over a year and a half later, STABLE, an artist studio and exhibition space located right off the Metropolitan Branch Trail in Eckington, is debuting their first gallery exhibition and throwing a grand opening celebration.

Those giant empty concrete rooms are now slices of studio spaces. They’re still full of light, but now they’re also covered with paint and car parts and tobacco leaves and spare piano equipment. Some of them are organized like little mini galleries, while others are jam packed with canvases and equipment. Wandering around the space feels like you’re hopping dimensions and peeking into another world. You never know if you’re going to walk into a room and see giant sculptures made of candy colored car parts or if you’ll be greeted by a carpet composed of egg shell slivers.

In the gallery space, all of that work comes together. Curated by Dr. Jordan Amirkhani, Dialogues is STABLE’s proof of concept. The exhibition, which pulls from every artist in the building, is wildly varied but still manages to feel cohesive. There are typographic installations, paintings inspired by childhood memories and a working piano that plays radio stations when you press down on its keys.

The differences in the work, whether its medium or subject or size, are what make the exhibition exciting. Knowing that some of this work was made under the same roof, that hammering and painting and threading and printing were done simultaneously, like some sort of art based orchestra, imbues the show with a special kind of power.

But there’s nothing quite like roaming the studios. If you can only see the exhibition, it’s still worth a trip to Eckington, but everything really clicks into gear when you see the spaces where the art is made. Watching other artists shoot the shit, pop their heads into each other spaces and share bigger studios makes STABLE’s vision feel alive. This isn’t a WeWork for artists, it’s a mad experiment.

STABLE’s grand opening soiree is Friday October 18.

Link to article

VIDEO of my talk at the National Gallery of Art was released today

Click HERE to watch

GRACE exhibition explores the intersection of art and motherhood

A very thoughtful article about my exhibition written by Janet Rems for the Fairfax Times

For photographer Caitlin Teal Price, 2010 initiated a profoundly transformative time, both personally and artistically. Returning to Washington, D.C., after years living and working in New York City and then earning her MFA at the Yale School of Art, she fell in love, married and became the mother of two sons, now six and four.

Her newest works, on view at the Greater Reston Arts Center through Nov. 24, are a visual “memoir” of her journey as a mother at the same time she was recapturing her productivity as an artist, living and working in a new environment with a whole new set of quotidian demands.

Known for her photographic collections of people and places, these new works focus instead on objects (twisted spoons, bits of metal, porcelain and plastic)—randomly collected by her sons on regular walks together. Although much different subject matter than her earlier people-oriented works, there are connections. Akin to still lifes, they likewise are carefully constructed portraits. Similarly, they also employ a distinctive use of crisp, intensely present light and shade.

“Photography is writing with light, and you’ve always used it well. … You almost forget it’s a photograph,” said Lily Siegel, GRACE executive director and curator.

Price—a rising artist whose work has been exhibited locally at the National Portrait Gallery, American University’s Katzen Arts Center and the Corcoran Gallery of Art—sat down with Siegel, at the gallery on Nov. 10 for a “Conversation” about her work’s new directions. Ruminating on the role of her sons, Price agreed that these new works function as a visual journal of their lives during this period. “It’s honoring them, their youth and their curiosity. It’s a nice representation of them, and, also as an artist, it’s taking a part of my life back.”

Something she keenly thought about as she was working, Price, though she doesn’t want to “pigeon-hole” herself as a “mom,” recalled that as her sons “treasure hunted,” a “light bulb suddenly went off.” She became attracted to these disparate bits and pieces as “objects of desire,” the idea developed of “making something ordinary precious.”

Price also owes the title of the exhibition, “Green Is the Secret Color to Make Gold,” to her sons. It was a notion that her then-five-year-old son repeated to his younger brother to convince him that green should be his favorite color. Noting its inadvertent “alchemical allusion,” it reinforced for Price “the possibility of the ordinary becoming extraordinary.”

Reiterating that the labors of both artists and parents is an “omnipresent concern” of the photographs in the exhibition,” Siegel further linked Price’s images to the 1920s Russian art movement, “Constructivism,” which conflated art and life and “celebrated technology and constructed art.”

Although these works “expose [Price’s] life to the viewer,” Siegel confessed that she had to resist reading specific narratives into them. Instead, she urged that they also be viewed as pure images “without symbolism.”

Now working with a digital camera, Price, looking to the future, suggested that she might return to the darkroom. “I found speed, but I lost process … the idea of labor,” she said.

The exhibition also includes three of Price’s first abstract works—two large-scale minimalist drawings, created with pigment and X-Acto blade, and a striking wall sculpture, “Circadian Drive,” constructed of 35 small, interconnected tiles (small enough for her to put in a bag and work on wherever her daily life took her), also created with pigment and X-Acto blade.

Compared by Siegel in concept to David Hockney’s 1980 “Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio,” in which Hockney painted his daily drive from memory, Price, in “Circadian Drive,” drew the repeated drive to her sons’ daycare with her eyes closed. While Hockney’s colors are “jubilant,” Price’s are a more subdued grey, black and white, extracted from a photograph of a rosemary bush along the route.

This was Price’s second formal conversation with Siegel about her art work. On Oct. 7, Price and Siegel talked about her new work and the GRACE exhibition with photographer and video artist, John Pilson, at the National Gallery of Art. Pilson also is senior critic and acting director of graduate studies for fall 2018 at the Yale University School of Art.

Green is the secret color to make gold

NEW WORK BY ME!!!

September 29 - November 24th 2018 // Greater Reston Art Center

Green is the Secret color to make gold

From A to B

Illuminating the obscured background of our lives is of primary interest to Caitlin Teal Price. Her recent drawing Circadian Drive (A to B in 35 squares)(2018) is a depiction of the route she drove every weekday for three years. She drew with her eyes closed. “Green is the secret color to make gold,” the title of this exhibition, is a phrase repeatedly recited by the artist’s 5-year old son to his younger brother to convince him that green should be his favorite color. Note the alchemical allusion to the possibility of the ordinary becoming extraordinary. The spoons and metal, plastic, and porcelain elegantly posed in her photographs were found on routine walks taken as a young family, thrust into pockets without thought of purpose or value.

Price has primarily been recognized as a photographer of portraits and of places. She has turned her attention and camera on the way others present themselves while managing to slyly amplify that which they are trying to keep hidden. She has put herself in uncomfortable positions to put her subjects at ease. The most recent body of work offers a new perspective on her oeuvre to date. Routine, from the French word for road, has always been a part of her practice. For her series Motel (2002), she documented the interior of roadside motels, sometimes occupied by women selected by the artist, sometimes reflecting occupants just out of view; Northern Territory (2006) depicts lives full of expectation of what may be just around the corner, a liminal state empty of optimism; Annabelle, Annabelle (2009–2012) takes the road as its subject and as its object—women are posed alongside freeways, parking garages, overpasses, and street-side facades.

In the newest work, a different path emerges. Price’s most recent series, Collection (2017–2018), and the accompanying drawings in this exhibition serve as a memoir of this moment in the artist’s life. After making Stranger Lives (2008–2015) and publishing her first book, of the series, Price found herself away from New York, settling into life in Washington, DC, and with a studio for the first time ever. Admittedly, it took her three years to figure out how to be productive in this new setting. She simultaneously had less time to herself, as she was a new mother, and more time to spend alone in a space dedicated to her art making. Time became something new to explore as she settled into the routine necessary to balance the life of an Artist Mother. She returned to photographing Birds (2008 and 2015) in the archive of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. She started making drawings. The first drawings were simple schematics, pencil on paper, that later became etchings. Though Price made prints, the metal etching plates are what she considers the final work. She found a tactile interest in material and the manual labor of creating things with her hands beyond the use of a camera, the manipulation of light. She began to reflect on her life and routine.

Circadian Driveis reminiscent of David Hockney’s Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio(1980). As Hockney painted his daily drive to the studio from memory, Price drew hers, the drive to her sons’ daycare, with her eyes closed—the title a lovely nod to the daily and the circadian rhythm controlling one’s levels of alertness throughout the day. Both works express a level of comfort and freneticism in the potential of the day. In each, the route becomes an unreliable horizon and the marks of the respective artist’s hand becomes the subject. Color and rhythm express the psychic energies of the drives. Hockney’s colors are jubilant, his marks animated, the joyful anticipation of reaching the studio apparent. Price’s colors are literal, extracted from a photograph of a rosemary bush along the route; her lines are expressions of hard work that add up to an ecstatic composition of satisfied labor.

Work and the labor of artists and parents, especially mothers, is an omnipresent concern in the drawings and the photographs in this exhibition. The images of Collection are directly influenced by Constructivism, the Russian art movement of the 1920s that espoused the conflation of art and life and celebrated technology and “constructed” art. Price found herself rich with discarded objects of technology gathered by her sons and a workspace ready to be utilized. It is easy to read the selection of objects as allegorical—twisted spoons as frustrated attempts at caregiving, the humble stake wreathed in gilded wire and elevated to trophy, the ambulatory wasp astride the coin of no value, porcelain and plastic, the high and low of domesticity. Instead, the story is written by the objects without symbolism. It is a tale of the quotidian. Price has bravely and generously exposed her life to the viewer with a gentle invitation to be self-reflexive and notice the things that define an existence.

- Lily Siegel, Curator and Executive Director @ The Greater Reston Art Center