*shown is a selection of images from the Stranger Lives series

STRANGER LIVES - The Monograph - was published by Capricious Publishing in 2016.

There are only a few copies left / GET YOURS HERE

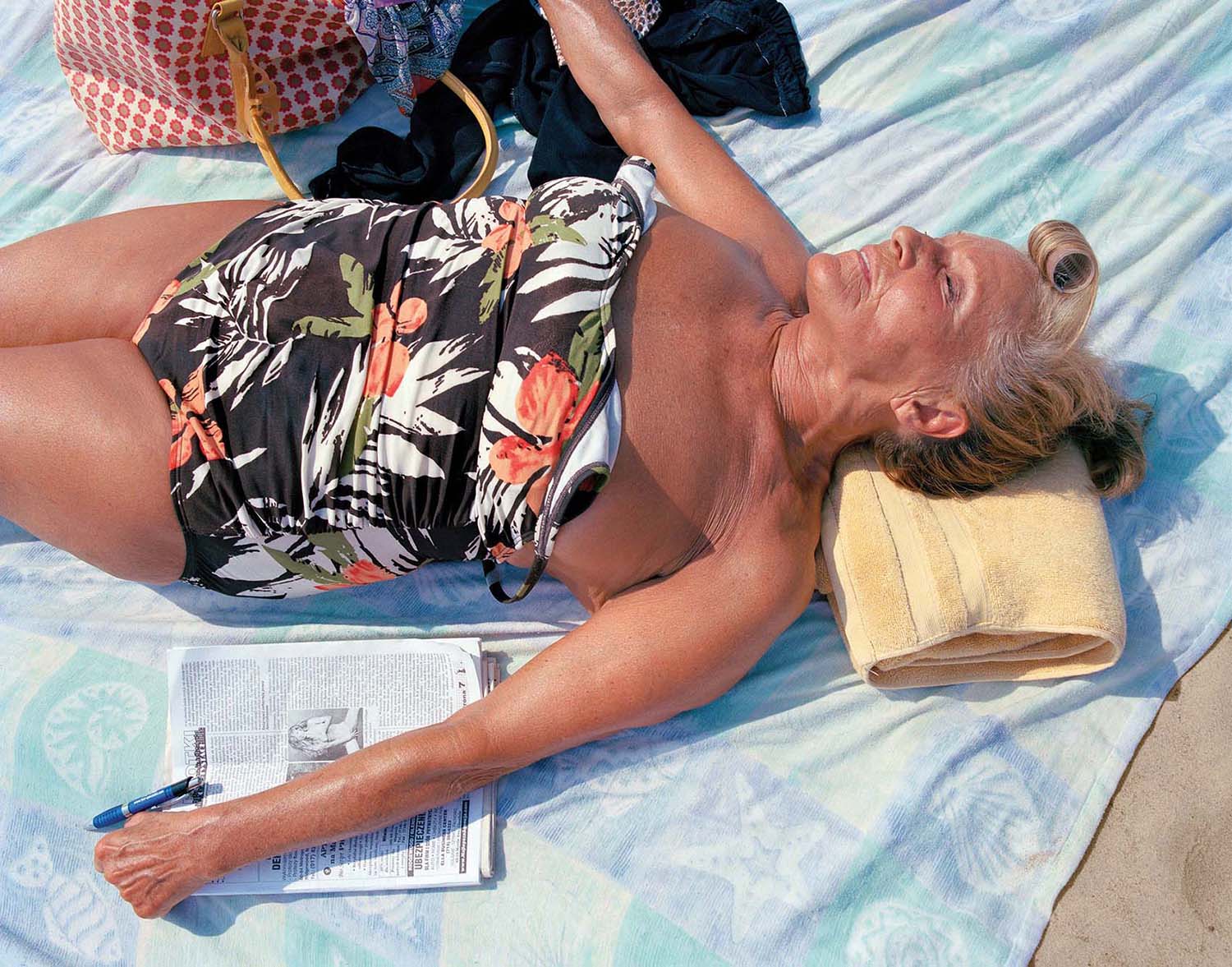

Stranger Lives is a vibrant taxonomy of sunbathing New Yorkers made on the stretch of sand between Coney Island and Brighton Beach between 2008 and 2015. Shot from above with a Mamiya RZ 6x7 camera and Kodak Portra film, these sharply focused portraits encourage you to stare, to wonder and to fantasize about the lives of strangers. The scars, veins and wrinkles on the skin, the pattern on the blanket, the style and placement of shoes and accessories, all can be read as signifiers of identity, class, and desire within a life beyond the frame. And yet with no offered horizon and a flattened perspective, our eyes remain hovered above the sunbathers, in specimen-like observation. The work plays with the legacy of the uncanny— making the familiar strange, and drawing the viewer into an intimate and voyeuristic exploration of object and body.

Image size, 42x52 inches

Stranger Lives / Katzen Art Center @ American University

Stranger Lives / Katzen Art Center @ American University

Essay by Dorothy Moss

published in the Stranger Lives Monograph

CLOSED-EYE SPECIMENS: Strangers on the Beach with Caitlin Teal Price

I really don't know why it is that all of us are so committed to the sea, except I think it is because in addition to the fact that the sea changes and the light changes, and ships change, it is because we all came from the sea. And it is an interesting biological fact that all of us have, in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch it we are going back from whence we came.

- John F. Kennedy, Americas Cup dinner 1962

Oiled bodies glistening in the heat of the sun conjure the scents of suntan lotion and salt air. My first reaction to viewing Caitlin Teal Price’s Stranger Lives was one of identification. Looking at the images brought back memories of growing up in the 1980s when sunbathing in the heat of the Texas sun allowed me a certain kind of escape as a teenager. I am drawn to something at once both timeless and edgy about the openness and relaxation in the bodies and on the faces of Price’s close-eyed subjects. The kind of defiance, a seizing of the moment for the sake of treating oneself to a seduction, and collectively escaping life’s stresses in a public setting is strangely exhilarating, perhaps made more so by the sense of voyeurism inherent in this project. Price’s approach to portraiture through Stranger Lives, focused predominantly on New York’s Coney Island and Brighton Beach, is beguilingly brilliant not only in its open approach to the individual but also in the ways the series conveys a sense of both personal freedom and communal experience. The body of work has a kind of leveling effect, reminding us of the way we are equalized and brought into community on a beach. The sand becomes a canvas for shared imaginings to the alluring, melodic sound of waves.

The Summer 2016 cover of ARTFORUM features a work by Barbara Kruger in which she takes apart a statement claiming that we are living in a “post-identity, post-race, post-gender, even post-human,” “pluralist and globalized” world. Kruger recently stated, “I love the everyday. I love the repetition of the everyday. . .I like the moments between events, and it’s during those moments that I create my work.”[1] Kruger’s ARTFORUM cover questions the “post-human” world that Price’s project also pushes against as she works within the “moments in between events.” Price represents our current moment through a probing, empathetic lens, leveling hierarchy and focusing on the individual as framed by a beach mat or towel, playing with the notion of types and the articulation of class but never losing sight of the specificity of the individual. In fact, each body tells a specific story. Each detail, each accessory, or tattoo, or scar says so much about the life pictured. As Price explains, “The inspiration for the project came from the people. I was lying on the beach myself one day and I really wanted to stare at everybody. I was (still am) interested in the juxtaposition of confidence and vulnerability and the way so much could be read into a person's life with just a few (rather intimate) details - what possessions they decided to surround themselves with, the scars and imprints on their skin, the way the color of the bathing suit matched the towel.”

Price’s deep sense of humanity emerges intensely in the dynamic she conveys between herself and the subjects of her Stranger Lives project. All parties (photographer, subject, and viewer) are vulnerable in this situation, but the vulnerability that we might expect her subjects to reveal is not evident in any of her photographs from this series. Self-consciousness seems not to have been an issue either on the part of the artist or her subjects or, if it was, the artist/subject relationship expresses such a willing and creative participation that the viewer sees only the comfortable part of the process. “Making these photographs without asking permission would seem so much scarier than it already is,” she has said. “Approaching a half-naked stranger and asking for a photograph is not the easiest thing I have ever done. But, in some ways, the thrill and risk of it makes it all the more exciting.” Groundbreaking photographer Lisette Model (1901-1983), whose famous photographs of a Coney Island bather from c. 1939, shares this approach. She was known to advise photographers, “Don’t click the shutter until the experience makes you feel embarrassed.”[2]

Price explains that the bodies “lay specimen-like” beneath the heat of the sun. She photographs them at midday, which allows for a bright light and even focus unhampered by a play of shadows. The notion of looking through the camera’s lens at a “specimen” calls to mind British Botanist, artist, and nature photographer Anna Atkins (1799-1871), whose cyanotypes of British algae, which she referred to as “flowers of the sea” were published in fascicles beginning in 1843. It was the first book to be photographically printed and illustrated and is a landmark publication in the history of photography. The synergy between Atkins and Price is located in their artfully scientific approach to the everyday. Price’s bodies like Atkin’s algae specimens, make the familiar strange through the clever individuality that emerges so powerfully when the specimens or bodies are put together as a series, an archive, a community.

Poet William Carlos Williams encouraged artists to champion “the local,” the ordinary. Price has found in her view of the local a sense of making the familiar strange and in that she stipulates the human condition; it is a perspective that anyone can access. Once we look closely at each photograph, it is impossible not to begin to imagine a life story as so many clues can be gleaned from the details in the portrait. Take for example, Price’s portrait of a woman who appears to be in her sixties wearing nothing but a white lacy bra, underwear, and reading glasses. She is lying on a small white towel with a plastic sheet under it, her black clothing is tucked behind her head as a pillow and one of her dress sandals is positioned to the right of her head. Looking like she might have just come from work or is perhaps on her lunch break, we can imagine that she disrobed spontaneously to take her place nonchalantly among the other sunbathers. The act of taking one’s clothes off in a public place is noteworthy and could even be shocking, but here in this particular image, wearing underwear in public fits perfectly within acceptable conventions of behavior. We glimpse a level of self-possession that is rare in the history of portraits of older women. This open, frank portrayal of a woman in her mature years reminds me of Alice Neel’s groundbreaking nude 1980 Self-Portrait (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution).

In a contrasting portrait, a deeply tanned sixtyish year old woman is shown coiffed and accessorized. Her pink leopard bathing suit becomes part of an elaborate tableau that includes a brown leopard-spotted towel accented with pink and purple decorative mandala shapes with paisleys. Adorned with a coral-colored manicure, a colorful beaded bracelet, a gold and silver watch, the woman’s left hand bears a wedding ring and her right hand is elegantly positioned holding a pair of white sunglasses. Her hot pink lipstick matches her bathing suit and the pinks pop against her suntanned skin. To the right of her head is a cotton bag that says, “Puerto Rico,” in red, white, and blue bubble letters referencing the shores of another beach. This is a woman who is in control of her beach presentation. She seems not only at home on the beach but in such command of the space she has carved for herself there that she projects a deep sense of her commitment to the artfulness of sunbathing.

The male version of this sun-worshipper is seen in a portrait of a man who appears to be in his late fifties or possibly early sixties. He is outstretched on a pink silk blanket wearing sky blue swim trunks. His chest hair sweeps over his torso thinly veiling the redness emerging from sunburn. With closed eyes, like all of Price’s sunbathing subjects, he surrenders to the camera in the same way he surrenders to the sun. What strikes me about this photograph, like many of the photographs in the series, is that there are no signs of the year or even the decade when this photograph was taken. It could be any time from the 1960s to now. There are no obvious markers of the current moment in terms of accessories or clothing. The portrait also speaks to the leveling of gendered codes of behavior that Price’s series achieves. There is a kind of seamlessness that surfaces between the photographs that capture subjects of both genders outstretched on beach towels, leveled by the sandy backdrop that forms a canvas. Male and female subjects are treated equally by Price to produce a project that is ungendered in the sense that the individual is portrayed without a focus on the performance of gender. As viewers, we see each individual as a person who has made specific choices and who embodies a set of life circumstances.

In another of Price’s beach specimens, a woman is lounging on a green towel with a green bikini and a green manicure. Her skin shows the stretch marks of pregnancy and is crowned with a star tattoo that encircles her belly button. A plastic child’s toy rests next to her right hand near a spray bottle and a cardboard carton of Tropicana orange juice. Nearby there is a black trash bag, black sunglasses, a newspaper, a floral cotton bag, and what appears to be a straw beach hat. She does not wear a wedding ring and does not appear to be with anyone. The interpretation of this one could go in various directions, but what I see is a mom, who is possibly single, with her eyes closed escaping her responsibilities to enjoy time to herself. Price lets the images open up to whatever we as viewers want to see in them. While they are about the individuality of the subject, they are also about the viewer. The closed eyes of each subject takes the agency of the subject away from the face and towards the pose. In that shift, the viewer is able to focus on what the body is saying and there is a sense of vulnerability that the photographer, the subject, and the audience share. Even looking at these images offers a contemplation of hierarchies of looking and notions of private versus public viewing. Since the subjects’ eyes are closed, viewers cannot help but wonder whether the subject knows he or she is being photographed and whether we should be looking at this private moment.

In part because of this play of hierarchies of observing, Price’s portraits are vessels for our own imaginings. They are for her as well. The strange is what compels her to the project, just as what the viewer finds strange might actually necessitate an impulse for seeking connections to make sense of the unexplained, at least in my experience, or for imagining how the story behind the life pictured connects to one’s own story. Not knowing that story—that open-endedness—is what brings the artist and viewer and subject into a shared space of existence where we are all in communion with the sea and each other and where we all walk that fine line together between public and private, individuality and community. As Price confirms, “I find that the less I know about the scene I am photographing the more authentic my exploration is and the more enriched my narrative becomes.”

Dorothy Moss

Associate Curator of Painting and Sculpture

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

[1] Eric Huang, “In Conversation: Barbara Kruger and Alexander Nemerov,” The Stanford Daily, 16 May 2016, http://www.stanforddaily.com/2016/05/19/in-conversation-barbara-kruger-and-alexander-nemerov/

[2] Martha Schwendener, “Lisette Model and Her Successors,” Aperture Gallery, review, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/19/arts/design/19gall.html